Existing problem

Reinforcement learning agents가 다양한 도메인에서 성공적인 결과물을 보이긴 하였지만, 여전히 그 실용성은 수작업으로 유용한 features를 만들어낼 수 있는 도메인이나 혹은 저차원의 state-space를 가진 도메인에 한정되어있다. Reinforcment learning이 실제 세계의 복잡도를 가진 문제에서 잘 작동하기 위해서는 아주 고차원의 sensory inputs으로 효율적인 representations를 얻어낼 수 있어야 하며 또한 이것들을 이용해 과거의 경험을 일반화하여 새로운 상황에 잘 적용할 수 있어야한다.

Objective

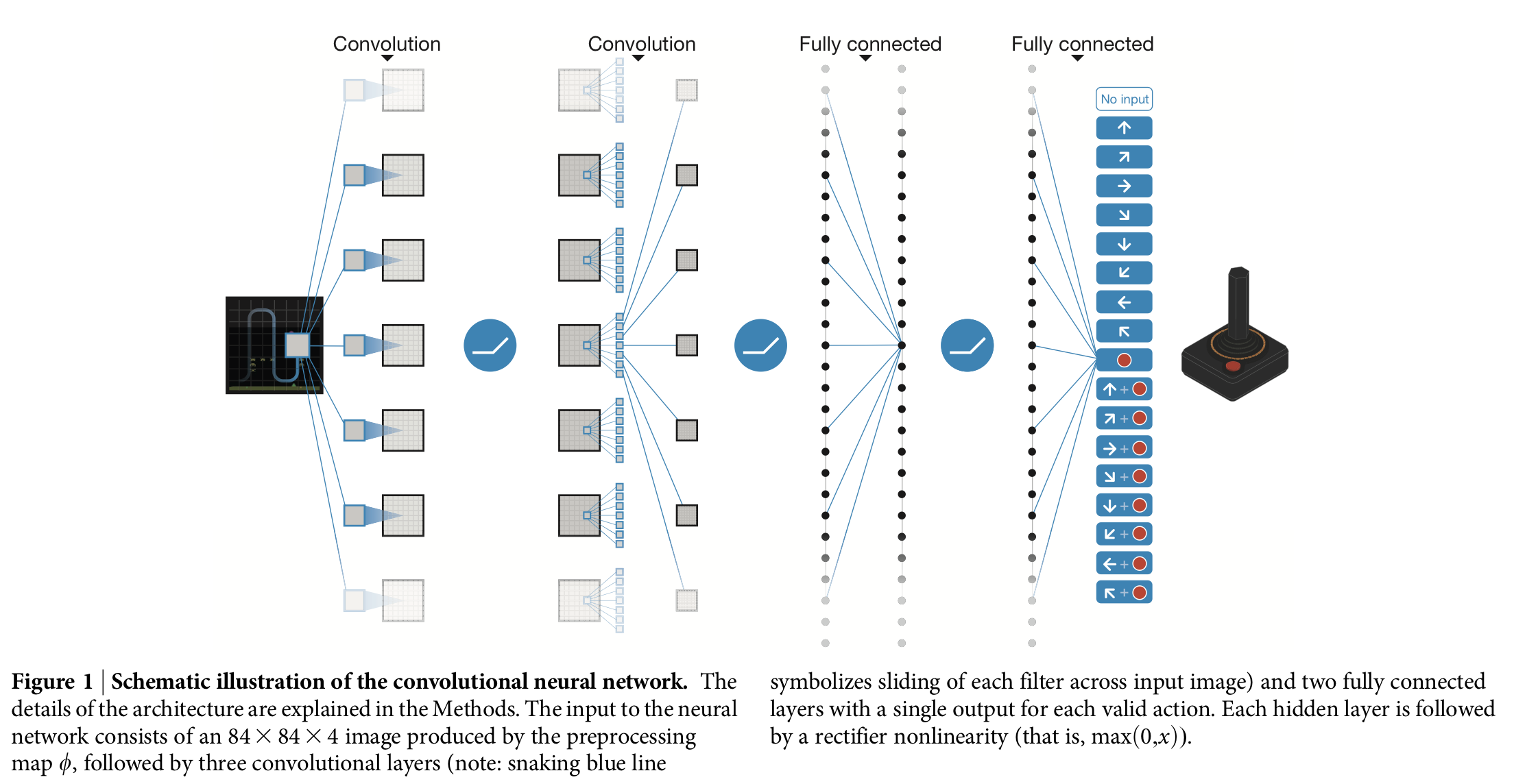

최근의 deep neural network의 발전으로 raw sensory data로부터 object category에 대한 컨셉을 곧바로 학습할 수 있게 되었다. 이 연구에서는 action-value function의 non-linear function approximator로 deep convolutional network라 불리는, 특히나 이례적인 성과를 보인 neural network architecture를 사용한다. 여기서 deep convolutional network는 convolutional filters를 층층이 쌓아서 receptive fields와도 같은 효과를 보이는 구조이다.

Methods

Agent는 환경과의 상호작용으로 발생하는 일련의 관측(observations), 행동(actions), 그리고 보상(rewards)을 통해 학습을 한다. Agent의 목적은 바로 누적보상을 최대화시킬 수 있는 행동을 선택하는 것인데, 이때 deep convolutional neural network를 이용해 optimal action-value function을 근사하도록 한다.

\[\begin{align} Q^*(s, a) &= max_{\pi} \mathbb{E} \big[ r_t + \gamma r_{t+1} + \gamma^2 r_{t+2} + \dotsc \mid s_t =s, a_t=a, \pi \big]\\ &=\mathbb{E} \big[ r_t + \gamma max_{\pi}Q^*(s_{t+1}, a_{t+1} \mid s, a)\big], \end{align}\]which is the maximum sum of rewards \(r_t\) discounted by \(\gamma\) at each time-step \(t\), achievable by a behaviour policy \(\pi = P(a \mid s)\), after making an observation (s) and taking an action (a).

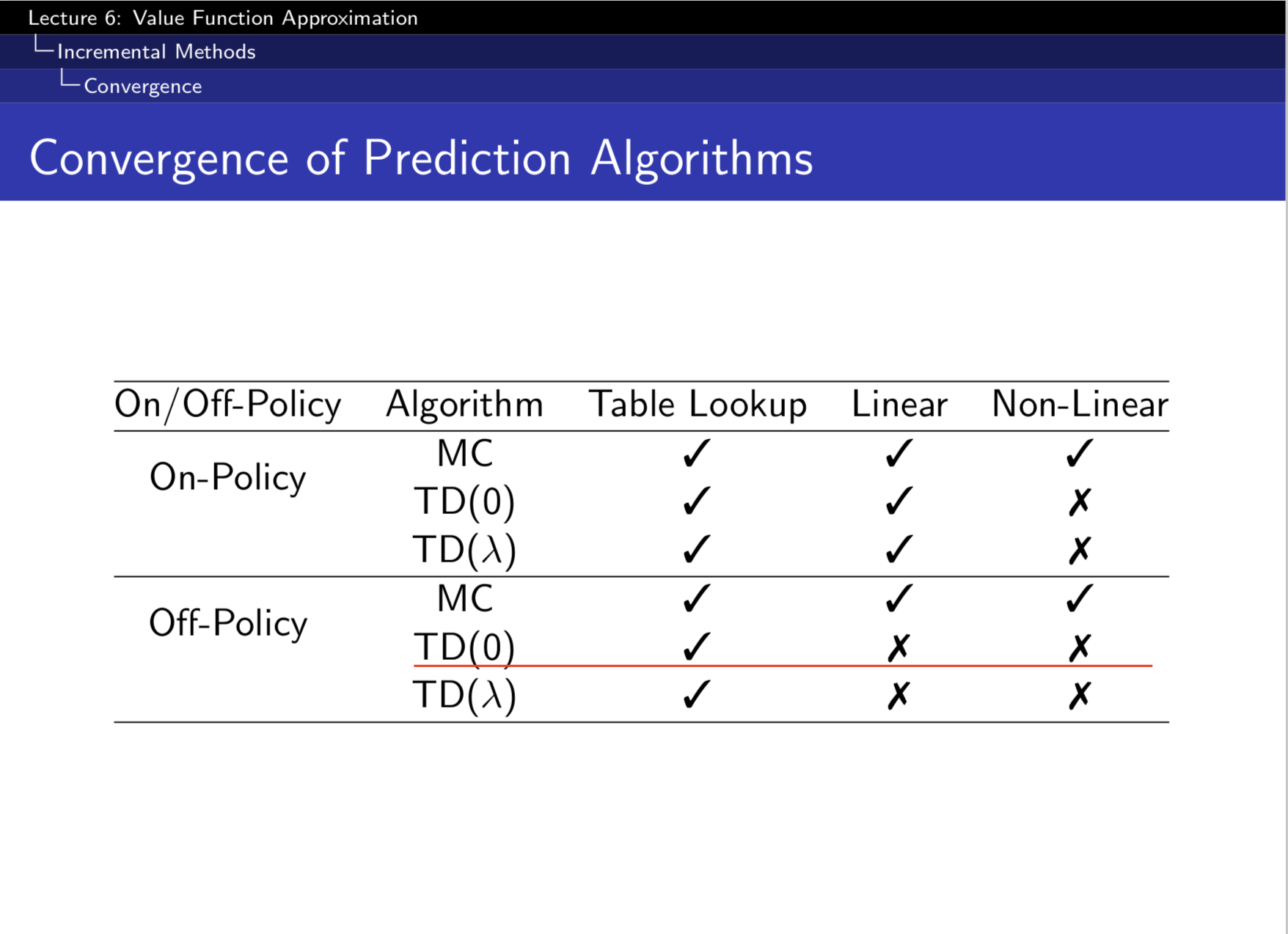

하지만 강화학습에서는 action-value(Q) function을 나타내기 위해 neural network같은 non-linear function approximator를 사용하면 학습이 제대로 되지 않는 것으로 알려져있다(아래그림[3]).

주로 다음과 같은 이유들 때문이다[4].

-

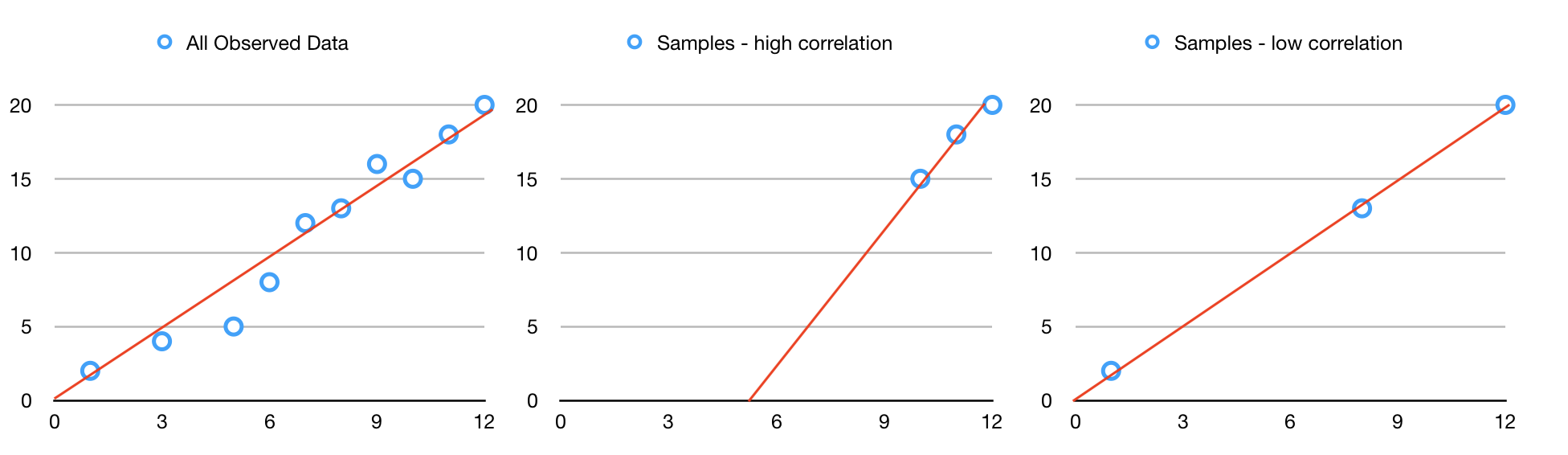

Correlation between samples: 강화학습에서의 학습데이터는 시간의 흐름에 따라 순차적으로 수집되고, 이 순차적인 데이터는 근접한 것들끼리 높은 correlation을 띄게된다. 만약에 이 순차적인 데이터를 그대로 입력으로 활용하게 되면 입력이미지들 간의 높은 correlation에 의해 학습이 불안정해질 것이다. 아래 linear regression의 예시를 보자.

좌측은 관측된 모든 데이터에 대한 linear regression의 결과이고, 중간은 domain에서의 correlation이 높은 데이터를 샘플링하여 얻은 linear regressoin의 결과이다. 마지막으로 우측은 domain에서의 correlation이 낮은 데이터를 샘플링하여 얻은 linear regression의 결과다. 중간과 우측의 결과들을 비교해봤을때 correlation이 낮은 입력데이터에 대한 linear regression의 결과가 모든 관측 데이터에 대해 좀 더 잘 들어맞는다는 것을 알 수 있다. 이 현상을 우리가 사용하게 될 deep convolutional neural network의 관점에서 다시 해석해보자[3]. 네트워크의 마지막 hidden layer를 통해 입력 \(s\)에 대한 representation vector \(x(s)\)를 얻을 수 있다고 할때, 여기에 어떤 action \(a\)에 대한 weight \(w_a\)를 내적하여 \(Q(s,a)\)가 얻어진다.

\[Q(s,a; \theta) = x(s)^T w_a\]

이때, objective function(loss function)은 parameter \(w_a\)에 대해 다음과 같은 quadratic form으로 표현될 수 있다.

\[\begin{align} L(w_a) &= \frac{1}{2} \big(Q^*(s,a) - Q(s,a;\theta) \big)^2\\ &= \frac{1}{2} \big(Q^*(s,a) - x(s)^Tw_a\big)^2\\ \end{align}\]

또한 \(w_a\)에 대한 stochastic gradient descent update는 다음과 같다.

\[\begin{align} \nabla{w_a}Q(s,a;\theta) &= x(s).\\ \Delta{w_a} &= \alpha\big(Q^*(s,a) - Q(s,a;\theta) \big)x(s).\\ \end{align}\]

where \(\alpha \in (0,1)\) is a step-size parameter.

만약 네트워크에 입력되는 states가 비슷하다면(highly correlated) 그에 대한 representation인 \(x(s)\) 또한 비슷한 모습을 띄게 될 것이고, \(w_a\)에 대한 업데이트가 다소 편향될 수 있음을 직관적으로 알 수 있다. 이 문제를 완화시키는 방안으로 본 논문에서는 experience replay(replay memory)라는 기법을 이용한다.

-

Non-stationary targets: MSE(Mean Squared Error)를 이용하여 optimal action-value function을 근사하기 위한 loss function을 다음과 같이 표현할 수 있다.

\[L_i(\theta_i) = \mathbb{E}_{s,a,r,s'} \big[ \big(r + \gamma max_{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta_i) - Q(s, a; \theta_i) \big)^2 \big],\]

where \(\theta_i\) are the parameters of the Q-network at iteration \(i\).

이는 Q-learning target \(y_i = r + \gamma max_{a'}Q(s', a'; \theta_i)\)를 근사하는 \(Q(s,a;\theta_i)\)를 구하려는 것과 같다. 문제는 \(y_i\)가 Q함수에 대해 의존성을 갖고 있으므로 Q함수를 업데이트하게 되면 target \(y_i\) 또한 움직이게 된다는 것이다. 이 현상으로 인한 학습의 불안정함을 줄이기 위해 fixed Q-targets를 이용한다.

Experience replay (Replay memory)

입력 데이터 간의 correlation을 줄이기 위해 사용되는 방법이다. Agent의 경험(experience) \(e_t=(s_t,a_t,r_t,s_{t+1})\)를 time-step 단위로 data set \(D_t = \{ e_1, \dotsc, e_t \}\)에 저장해 둔다. 그리고 이 data set으로부터 uniform random sampling을 통해 minibatch를 구성하여 학습을 진행한다\(\big( (s,a,r,s') \sim U(D) \big)\). 이 방법을 이용하면 minibatch가 순차적인 데이터로 구성되지 않으므로 입력 데이터 사이의 correlation을 상당히 줄일 수 있다. 또한 과거의 경험에 대해 반복적인 학습을 가능하게 한다[3]. 논문의 실험에서는 replay memory size를 1,000,000으로 설정한다.

Fixed Q-targets

Non-stationary targets 문제를 완화하기 위해 사용되는 방법이다. \(Q(s,a; \theta)\)와 같은 네트워크 구조이지만 다른 파라미터를 가진(독립적인) target network \(\hat{Q}(s,a; \theta^{-})\)를 만들고 이를 Q-learning target \(y_i\)에 이용한다.

\[\begin{align} y_i &= r + \gamma max_{a'} \hat{Q}(s', a'; \theta_i^{-}).\\ L_i(\theta_i) &= \mathbb{E}_{(s,a,r,s') \sim U(D)} \big[ \big(r + \gamma max_{a'} \hat{Q}(s', a'; \theta_i^{-}) - Q(s, a; \theta_i) \big)^2 \big],\\ \end{align}\]in which \(\gamma\) is the discount factor determining the agent’s horizon, \(\theta_i\) are the parameters of the Q-network at iteration \(i\) and \(\theta_i^{-}\) are the network parameters used to compute the target at iteration \(i\).

Target network parameters \(\theta_i^{-}\)는 매 C step마다 Q-network parameters(\(\theta_i\))로 업데이트된다. 즉, C번의 iteration동안에는 Q-learning update시 target이 움직이는 현상을 방지할 수 있다. 논문의 실험에서는 C값을 10,000으로 설정한다.

Gradient clipping

Network의 loss function \(\big( r + \gamma max_{a'}Q(s', a'; \theta_i^{-} - Q(s, a; \theta_i) \big)^2\)에 대한 gradient가 -1 보다 작을때는 -1로, 1보다 클때는 1로 clipping해준다[2]. 이러한 방식은 loss function이 일정 구간 내에서는 L2로, 구간 바깥에서는 L1으로 동작하게 하는데, 이는 outlier에 강한 성질이 있으므로 학습과정을 좀 더 안정적으로 만들 수 있다. Huber loss[7]와 기능적으로 동일하기 때문에 구현시에는 loss function을 Huber loss로 정의하기도 한다[8].

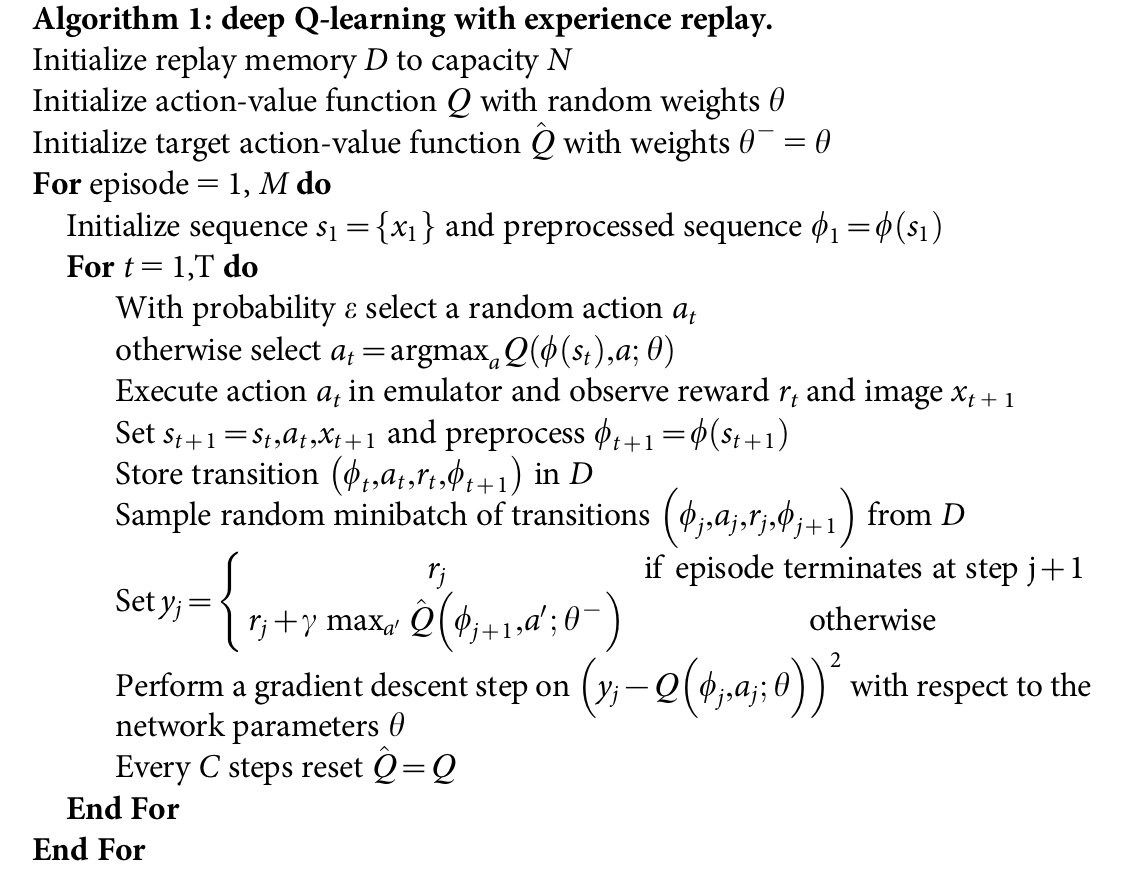

Algorithm

참고로 위 알고리즘에는 gradient clipping에 대한 내용은 언급되어있지 않다.

Model architecture

- Input: 84x84x4 (by preprocessing map \(\phi\))

- 32 convolutional filters of 8x8 with stride 4 followed by a rectifier non-linearity

- 64 convolutional filters of 4x4 with stride 2 followed by a rectifier non-linearity

- 64 convolutional filters of 3x3 with stride 1 followed by a rectifier non-linearity

- Fully connected layer with 512 nodes + a rectifier non-linearity

- Fully connected linear layer with a single output for each valid action

Preprocessing

Atari 2600은 210x160 pixel의 colour image를 초당 60프레임 정도로 화면에 출력한다. 출력된 화면에 대해 다음과 같은 전처리 과정을 거쳐 84x84xm의 입력데이터를 얻는다[6]. (논문에서는 m을 4로 설정)

- 이미지의 크기를 (210, 160)에서 (84, 84)로 변환

- RGB 이미지를 grayscale로 변환

- 연속된 이미지들 중 매 k번째에 위치한 이미지들만 선택된다(Skipped frame).*

- 3에서 선택된 이미지와 그 앞에 위치한 이미지에 대해 pixel-wise(component-wise) maximum을 취해준다.**

- 1-4의 과정을 거친 이미지들을 m개 만큼 쌓으면 네트워크의 입력으로 사용될 수 있는 하나의 상태(state)가 된다.***

*모든 frame을 전부 입력으로 활용하는 것은 자원 낭비이기 때문이다. 매 k번째의 이미지만 입력으로 이용하고 skipped frame에서는 가장 마지막에 선택된 action이 반복된다. 논문에서는 k를 4로 설정했다.

**Atari 2600은 화면에 한 번에 표시할 수 있는 sprites가 단 5개 뿐이어서 짝수 프레임, 홀수 프레임에 번갈아서 표시하는 것으로 여러개의 sprites를 화면에 보여줄 수 있었다. 연속된 두 이미지에 대해 component-wise maximum을 취해줌으로써 이를 한 이미지에 모두 표시할 수 있다.

***1-4의 과정을 거쳐서 얻은 이미지가 \(x_1, x_2, \dotsc, x_7\)이라고 했을때 s1=(\(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4\)), s2=(\(x_2, x_3, x_4,x_5\)), \(\dotsc\) , s4=(\(x_4, x_5, x_6,x_7\)). 즉, 연속된 states 간에는 overlapping이 발생한다.

Training details

Reward

게임마다 점수의 단위가 천차만별이다. 이 논문에서는 모든 positive reward에 대해서는 1로, 모든 negative reward에서는 -1로, unchanged reward에 대해서는 0으로 그 값을 clipping한다. Reward를 clipping하는 것으로 여러 게임에 대해 같은 learning rate로 학습하는 것이 가능해진다.

Episode

Atari 2600 emulator를 통해 life counter를 전달받을 수 있다. 이는 학습 과정에서 episode의 끝을 표시하기 위해 사용된다.

Epsilon

Behaviour policy는 \(\epsilon\)-greedy 방식이다. \(\epsilon\) 값은 1.0으로 시작하여 최초 백 만 프레임동안 선형적으로 0.1까지 감소하고 이후에는 그 값을 유지한다.

ETC

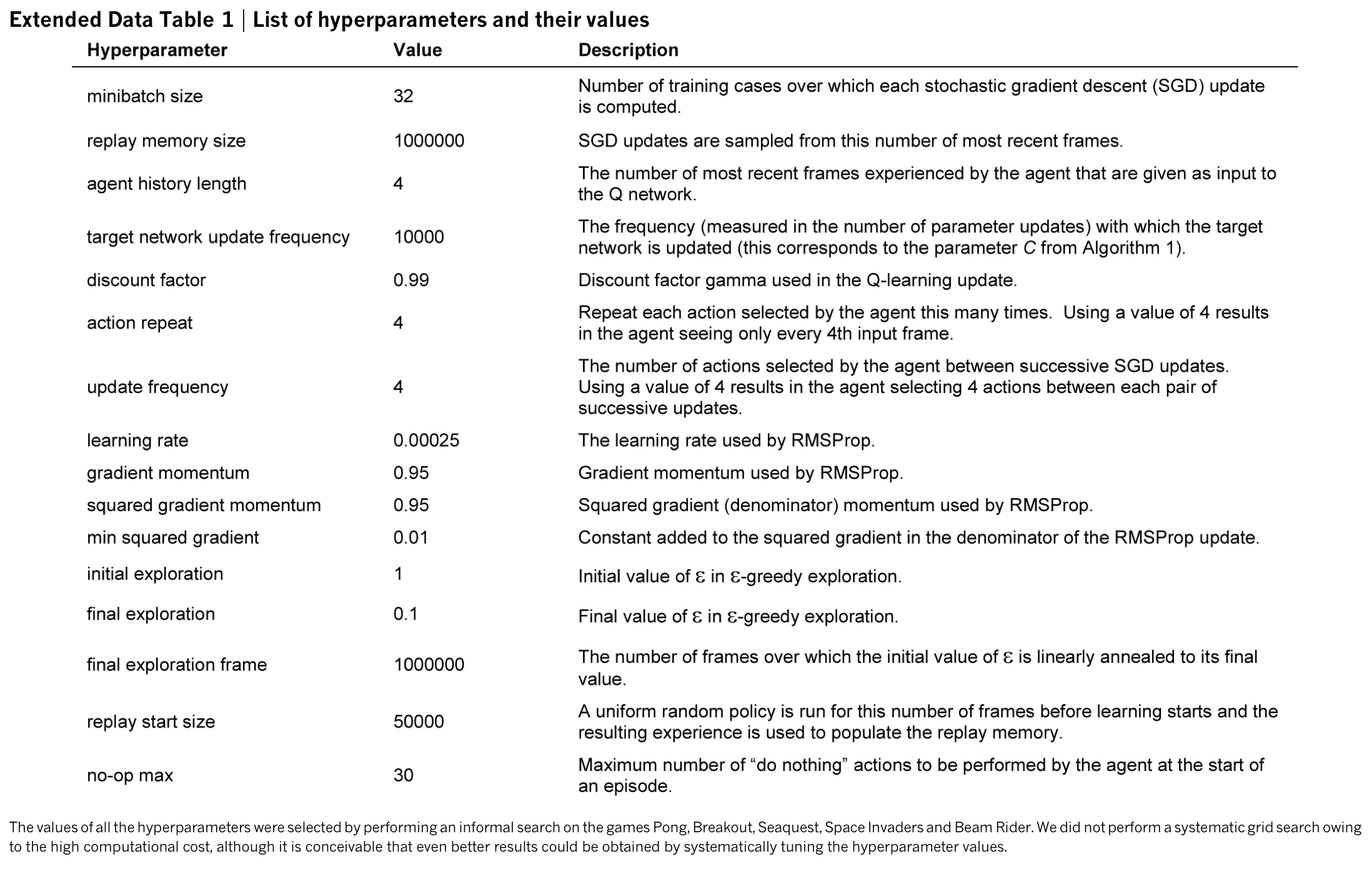

기타 정보는 아래 테이블을 확인하자.

Experiments

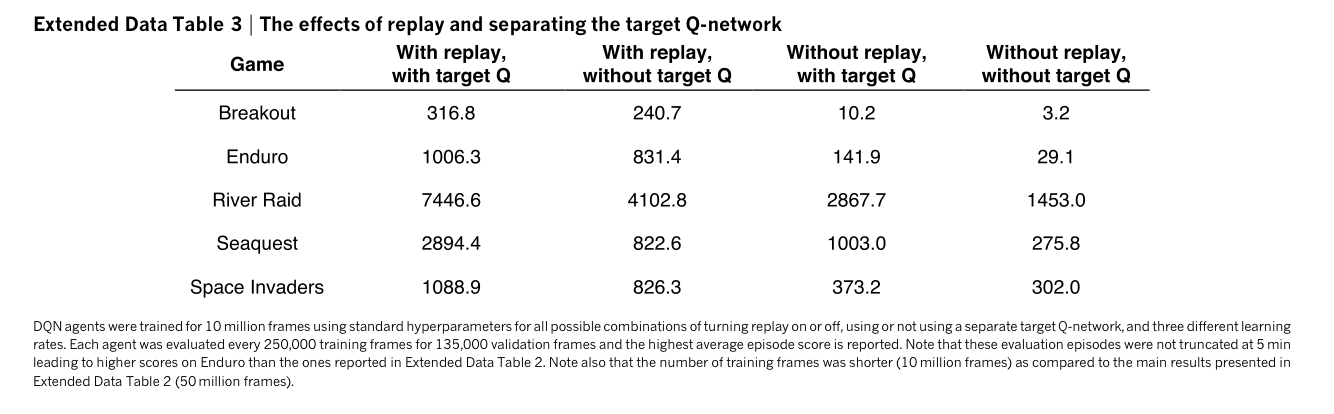

Extended Data Table 3에서는 replay memory와 target Q-network의 사용 유무에 따른 퍼포먼스의 차이를 비교한다.

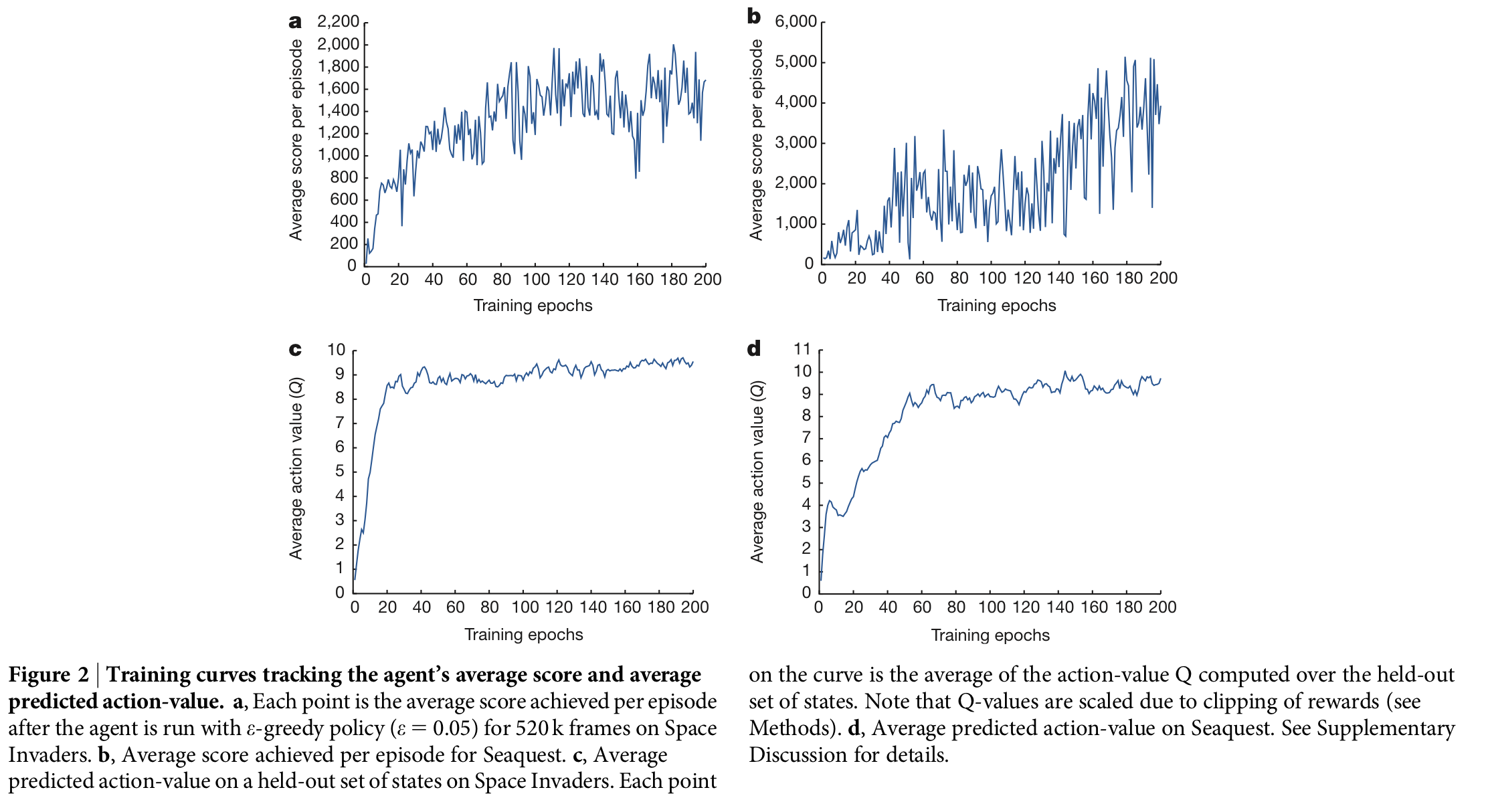

Figure 2는 average action value가 점차 수렴함을 보여준다.

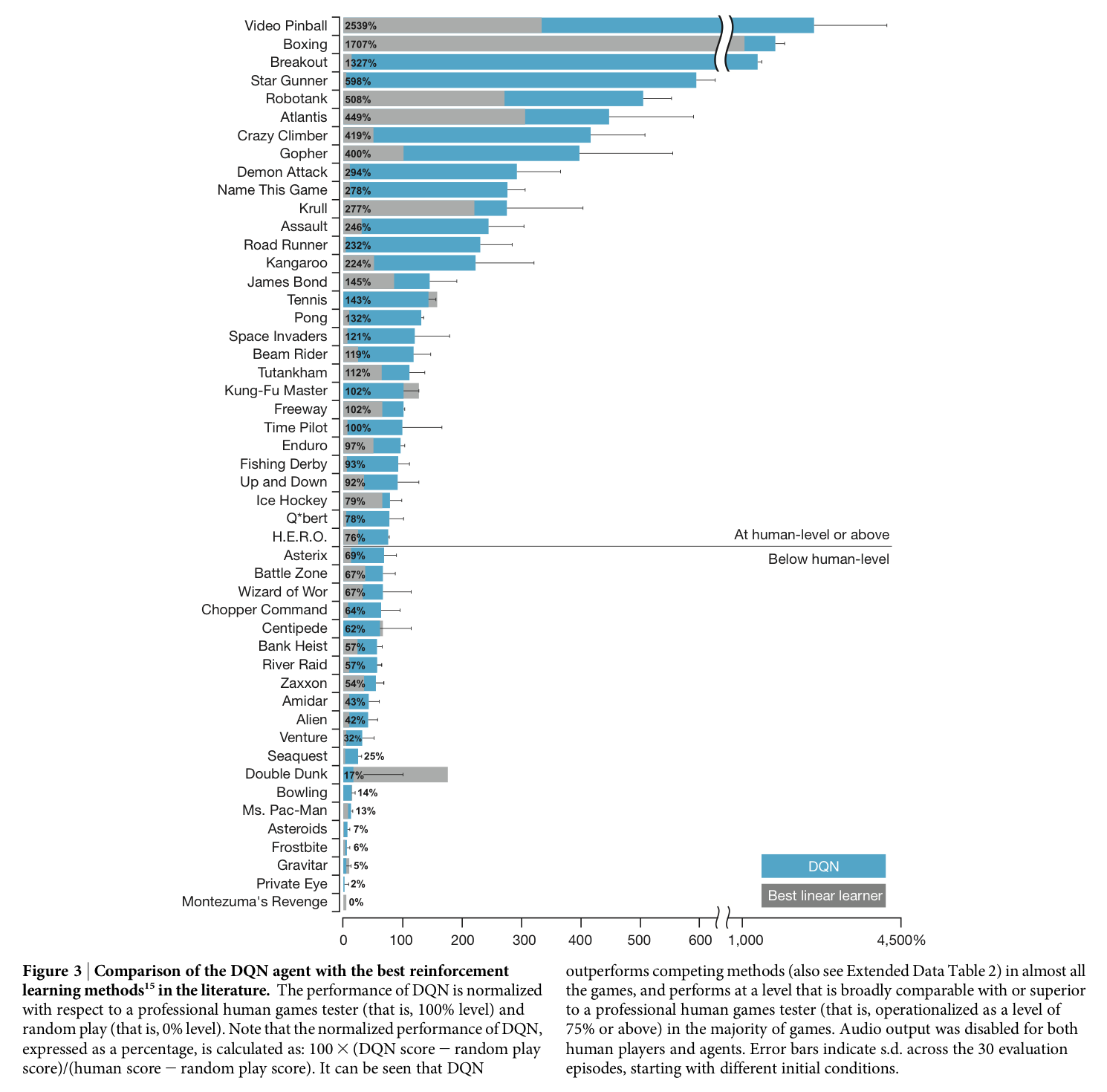

Figure 3는 professional human games tester와 random play 그리고 DQN의 성능비교 표이다. 특히 49개의 게임중 75%에 해당하는 29개의 게임에서 인간의 퍼포먼스를 상회한 것이 매우 인상적이다.

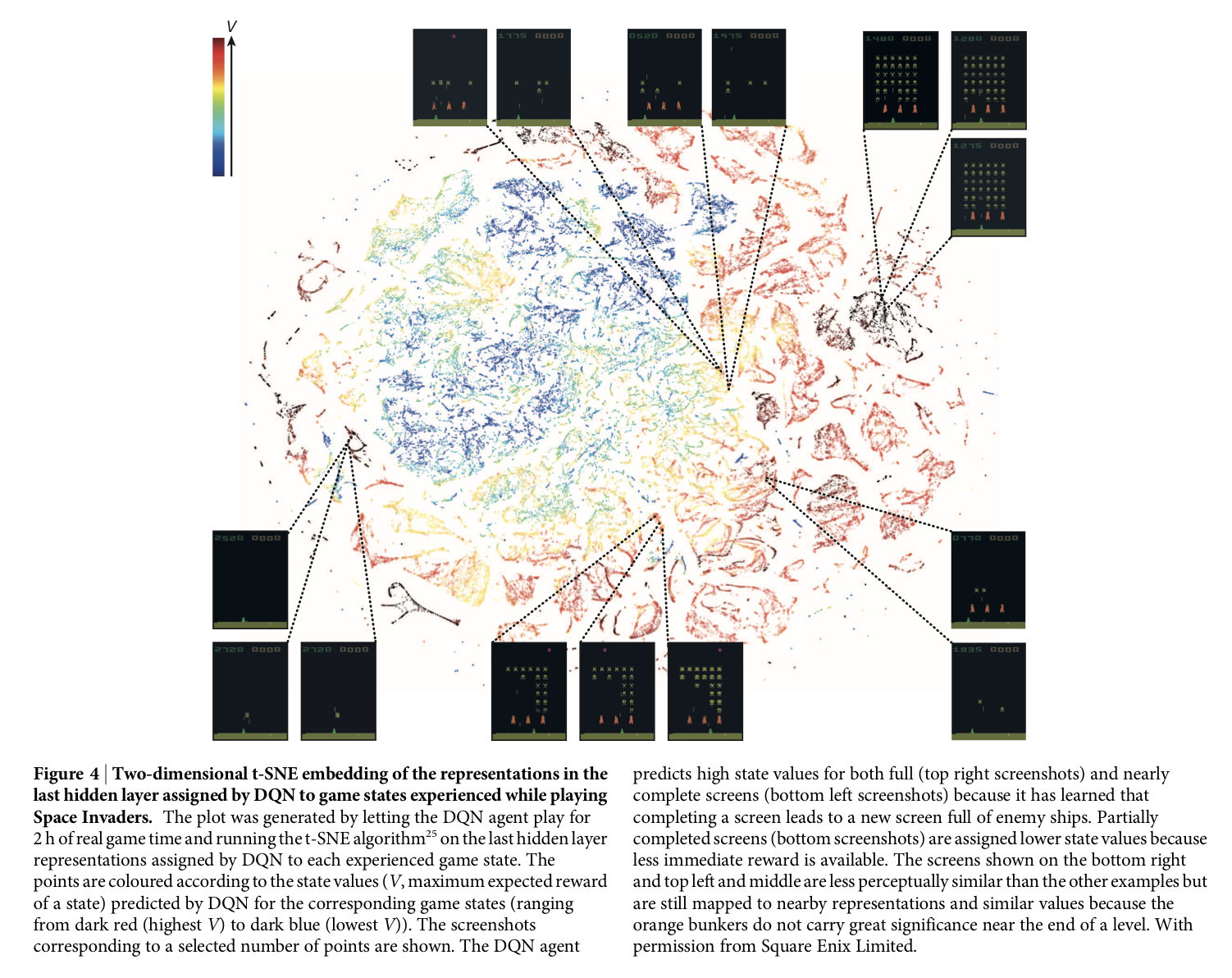

Figure 4는 expected reward가 엇비슷한 서로 다른 states에 대해, 네트워크가 상당히 유사한 representation을 나타냄을 보인다.

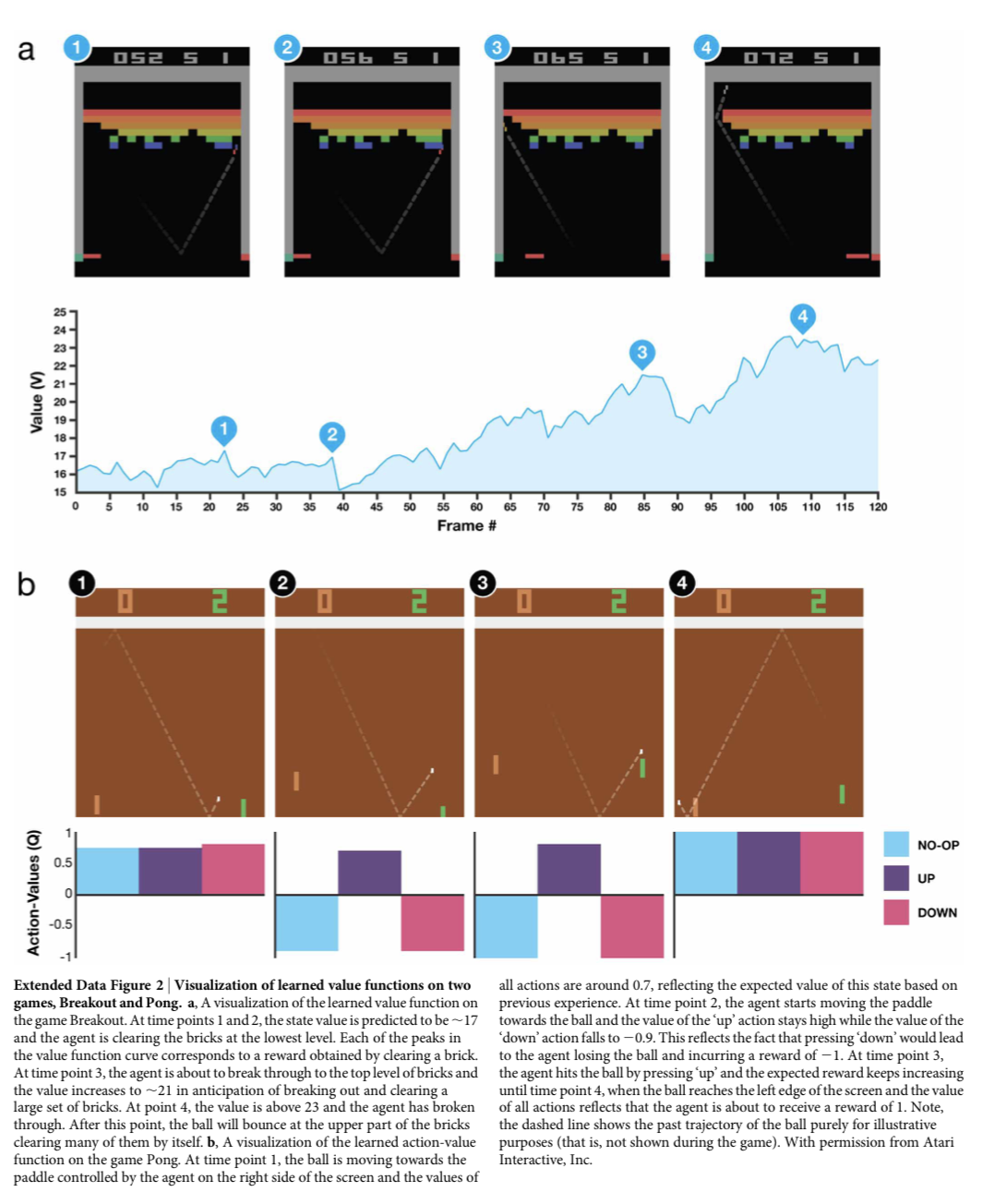

Extended Data Figure 2는 Breakout과 Pong에서 각 상황에 따라 변화하는 value / action-value를 보여준다.

Conclusion

(원문의 결론 서두를 요약)

In this work, we demonstrate that a single architecture can successfully learn control policies in a range of different environments with only very minimal prior knowledge, receiving only the pixels and the game score as inputs, and using the same algorithm, network architecture and hyperparameters on each game, privy only to the inputs a human player would have, notably by the successful integration of reinforcement learning with deep network architectures.

References

- Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D. et al. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature, 518 (7540), pp. 529-533.

- Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D. et al. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. [Code]. Available at: https://sites.google.com/a/deepmind.com/dqn [Accessed 18 May. 2018]

- Silver, D. (2015). Lecture 6: Value Function Approximation. [Video]. Available at: https://youtu.be/UoPei5o4fps [Accessed 17 May. 2018].

- Kim, S. (2017). Lecture 7: DQN. [Video]. Available at: https://youtu.be/S1Y9eys2bdg [Accessed 17 May. 2018].

- Kim, S. (2017). PR-005: Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning (NIPS 2013 Deep Learning Workshop). [Video]. Available at: https://youtu.be/V7_cNTfm2i8 [Accessed 17 May. 2018].

- Seita, D. (2016). Frame Skipping and Pre-Processing for Deep Q-Networks on Atari 2600 Games. [Online]. Available at: https://danieltakeshi.github.io/2016/11/25/frame-skipping-and-preprocessing-for-deep-q-networks-on-atari-2600-games [Accessed 18 May. 2018].

- Boyd, S. and Vandenberghe, L. (2004). Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press, p. 299.

- Karpathy, A. et al. (2016). A bug in the implementation. [Online] Available at: https://github.com/devsisters/DQN-tensorflow/issues/16 [Accessed 18 May. 2018].